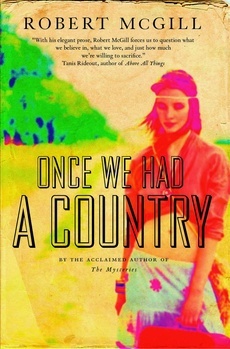

Once We Had a Country: Q&A

Q: How would you summarize your novel in one sentence?

In 1972, a young American woman moves to the Niagara Peninsula and struggles to remake her life on a commune after becoming estranged from her father, a missionary in Laos.

Q: Why write about 1972?

It was a year of iconic events: Nixon’s re-election, the Munich Olympics, the Watergate break-in, Jane Fonda in North Vietnam, the famous photo of Kim Phuc burned by napalm and running naked down a road. It was the year George Carlin was charged with obscenity for “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television.” There was Fischer vs. Spassky in Iceland; there was Apollo 17, the last manned mission to the moon.

In Canada, it was the year of the Summit Series and a federal election that reduced Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals to a minority government. 1972 was the end of a spectacular period in Canadian history that had started with Expo ’67 and the Centennial and that included the October Crisis, as well as the legalization of homosexuality and contraception. The contemporary idea of Canada as a refugee haven and non-militaristic nation comes largely from that era. I was drawn to the period because it seemed to mark Canada’s coming of age.

More personally, it was my parents’ era: they were university students from 1968 to 1972. But they hadn’t taken part in any of the big historical events of the time—or at least, that was my impression. Recently, I talked to them about things, and it turns out they were in Montreal during the October Crisis.

So when I set out to write about 1972, I was interested in the connections between history and the lives of people who seem to be set apart from it, those whose engagements with history come as most North Americans’ do—through things like TV and newspapers. In the novel, Maggie and the others on the farm seem isolated, yet they keep brushing up against big historical moments. I wanted to capture the intersections of history and everyday life, as well as the gaps between them.

Q: Why focus on a woman moving to Canada?

By now, the story of US draft-dodgers in Canada during the Vietnam War is pretty familiar. But many of the most interesting Americans who moved to Canada during the war were women: urban planning guru Jane Jacobs, journalist Diane Francis, novelist Joyce Carol Oates. My literary agent in Toronto, Denise Bukowski, moved to Canada from the States then.

And as the war was going on, so was Women’s Liberation. In Canada, there were women-only communes near Toronto, near Winnipeg, near Vancouver and Montreal. I wanted to return to that history by imagining what it might have been like to be a young woman on a commune in that time.

Q: How long did it take you to write the novel, and what kind of research did you do?

It took six years. The first couple of years were spent learning about the Vietnam War, Laos, migrant worker programs, and cherry farming, among other things. I read books and articles, watched films from the time, and talked with people who’d moved to Canada during the Vietnam War, as well as with people who’d lived on communes.

Once I’d completed most of the research, it took me another two years to finish the first draft. Then I spent two more years editing and fine-tuning the story.

Q: What were the challenges of writing a novel set in 1972?

I wanted to have the characters connected to history, noticing history, but I didn’t want the novel to turn into a history book. So bringing in historical references required a certain delicacy. Similarly, I wanted to avoid a situation where everyone was saying “groovy” and wearing tie-dyed clothes.

Another challenge was that parts of the novel refer to technology, and technology changes quickly. For instance, Super 8-mm film cameras had the capability to record sound in 1973 but not in 1972. Once I discovered that fact, I made it important to the plot. I like historical novels in which the particularities of the time are key to the action, so that the story couldn’t happen in the same way if it were set at in a different decade, or even in a different year.

Q: Why set the novel on the Niagara Peninsula?

It’s such an intriguing place—at once very Canadian and very globalized. It’s the site of important Canadian victories in the War of 1812, and it’s the home of Niagara Falls, a great Canadian symbol. At the same time, it has long been one of the most “American” regions of Canada, with all the people crossing the border and with the saturation of the area by US radio and TV stations. Also, it’s a place with a large number of seasonal migrant agricultural workers from the Caribbean and Mexico.

My grandparents lived on the Niagara Peninsula when I was a kid. I grew up several hours to the north, in a place where there were only two TV channels. On visits to my grandparents, one of the things that excited me was the fact that they had cable—about thirty channels, most of them American. I’d get up at 6 am and spend all day watching television. My grandfather liked to say I was “studying.” And I think that in a way, I was. I was learning about the USA.

Q: Did you realize how much sex there is in your novel?

I did notice there’s a lot. The story’s about a couple in their twenties living on a commune, so a certain amount of sex seemed necessary for the sake of realism.

But also, 1972 was a year full of sex. A quarter of all college men in the USA were buying Playboy. It was the year of Deep Throat. It was the year that the US Supreme Court heard Roe v. Wade. It was the year of a scandal over the image of a naked man and woman engraved on the side of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft.

And increasing numbers of people had Super 8-mm film cameras. The era of do-it-yourself pornography had begun. To have technology mediating sex in that way changed how people understand intimacy and privacy. We’re still trying to figure out how to deal with the repercussions. In the novel, there are a few dramatic consequences.

There’s one scene that’s rather explicit. It’s a scene that draws attention to how dangerously fragile the border between privacy and exposure has become. A friend of mine read an early draft of the novel, and she reached the scene while she was in a Mexican airport. She got so engrossed that she missed her flight. I felt bad for her, but I have to admit, hearing about it was just about my proudest moment as a writer.

Q: Did writing the book change you?

I became both more admiring and more sceptical about the countercultural politics of the Vietnam War era. Before I started my research, I knew the stereotypes of the hippies—the sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Once I began researching the period, though, I saw how profoundly many of those people were trying to change the world and how carefully they thought about what they were doing, both publicly and in their daily lives.

I also realized that many of those same people were still very conservative in certain ways, especially in terms of gender and sexuality. The male chauvinism and homophobia of the era were pretty horrendous. So the book helped me to see more clearly the value of being sceptical about one’s own positions and assumptions. It also helped me to appreciate better how taking a big risk in one’s life—by, say, moving to a commune in a different country, as Maggie does—might lead somebody to compensate through greater conservatism in other ways.