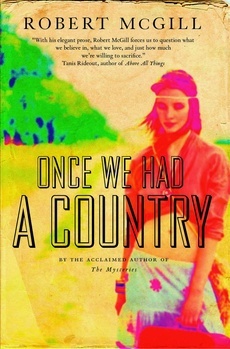

Once We Had a Country: Deleted Scene #3 — The Missus

This scene, from late in the novel, was cut because it had too much overlap with another scene involving Maggie and a teenager.

------

This time there are plenty of places to park. It isn’t a surprise, for who besides Maggie would think to visit Niagara Falls on a drizzly weekday morning in the middle of December? Only the desperate and dispossessed stroll the promenade beside the falls—alcoholics, racetrack losers. Sitting on a bench with the camera beside her, she watches a pair of teenagers walk past, the boy a few yards ahead, the girl dragging her feet, her belly’s protrusion impossible to hide. Both of them are without jackets, and neither carries an umbrella. They don’t even gaze at the cataract, as if it doesn’t exist or doesn’t matter. Periodically, the boy turns to check on the girl, and each time she smiles at him. On their own, though, they both look miserable, deep in thought. Maggie’s inclination is to feel sorry for them, but when the girl catches her staring at them from her bench, she stares back with derision, for there’s Maggie without an umbrella, either, and without a baby coming or someone to coax smiles from her and worry over her wellbeing. She wonders if George Ray has ever seen Niagara Falls, and she regrets never offering to take him there.

Once the teenagers have passed out of sight, Maggie goes to the railing just above the falls. Her father brought her to this place when she was nine, and, for weeks afterward, she had dreams where she was in the river being swept toward the brink. They always ended just as she began to plummet. She never told him about these dreams, worried he’d blame himself for having taken her there.

Removing the camera from its case, she switches it on and zooms in until the frame is filled with cascading water. She tries to imagine how it will look projected on the wall, grainy whiteness tumbling down whiteness, the whole thing silent because she left the tape recorder at home. Rain starts to collect on her lens, and she knows the shot will be ruined by the droplets, but she doesn’t want to stop.

As she’s about to put the cap back on and start home, she sees the teenagers returning along the promenade. Without thinking, she turns the camera on them. They become smeared grays under iridescent cloudbanks. The boy walks past Maggie without even noticing her, but as she trains the lens on the girl, his voice cries out.

“What’re you doing? Don’t poke that thing at her!” She swivels and catches his outraged face through the viewfinder. Then she turns off the camera and lowers it while he draws closer, still looking vexed, but curiosity showing on his face.

“You with the TV?” he asks, and she reassures him that she isn’t, feeling a pity for a boy so callow. She tells him that filming is just a hobby. “Funny hobby,” he replies. “We come up here for some privacy.” As he says this, he seems to have an idea. “It’s worth something, ain’t it, taking our picture like that?” He says it with a sly belligerence. In a graver tone, he adds, “We’re a little hard up right now. The missus—” He looks over to the girl, who’s watching them both, and who puts her hands protectively over her swollen stomach. “—well, you can see for yourself about the missus.” For the first time, Maggie notices the wedding ring on the girl’s hand.

Maggie reaches into her pocket. She has a single ten-dollar bill and a few coins. It’s the last of her money. There’s no more under the mattress or in the bank. There’s hardly any gas left in the camper, and the fridge is almost empty.

Before she can stop herself, she gives the boy the bill. He turns it over in his hand and looks disappointed.

“We’re not looking for handouts,” he says with a glower, though he still holds her money in his fist.

Behind the wheel of the camper, she sits awhile and imagines telling Brid what has just transpired. She’s pleased to think that Brid will enjoy hearing it, but this thought is disconcerting, because she didn’t think Brid’s enjoyment was so important to her.

Just as she’s about to start the engine and drive off, there’s a soft tap on the window. Through the rain-drenched glass stares the face of the teenage girl. Maggie opens the door to greet her.

“I just wanted to say thanks,” says the girl. She glances back toward the boy, who’s watching from the edge of the parking lot, then drops her voice and looks down at her belly. “It isn’t his, you know. He’s going to let people think it is, but isn’t. Pretty swell of him, huh?”

Maggie agrees that it’s pretty swell. She waits for more to be said, but the girl has nothing else to add; she only turns back toward the boy and trudges off to him, still dragging her feet.